Finally Actually (Hopefully) Learning Rust

The current events

As I mentioned in my post about prototyping a ESP32 based beaconDB Scanner, I've been looking to use Rust for the actual version of the project after the prototype. My intention was to write up this post after I had gone through several resources to be properly productive in the language. [1]

However, in my post on practicing writing I mentioned how I'm enjoying the writing format of taking some notes from a current project and pairing that with commentary on a current event. See my post on OpenTofu vs Terraform for an example. So I'm putting this post out sooner than I thought because of current events:

(From Adafruit on November 19th)

Qualcomm-owned Arduino quietly pushed a sweeping rewrite of its Terms of Service and Privacy Policy, and the changes mark a clear break from the open-hardware ethos that built the platform...

...users are now explicitly forbidden from reverse-engineering or even attempting to understand how the platform works unless Arduino gives permission.

Now after digging in further, this seems to only apply to their cloud services. [2],

Then there's Arduino's reply on November 21st [3] :

Let us be absolutely clear: we have been open-source long before it was fashionable. We’re not going to change now. The Qualcomm acquisition doesn’t modify how user data is handled or how we apply our open-source principles.

...

Restrictions on reverse-engineering apply specifically to our Software-as-a-Service cloud applications. Anything that was open, stays open.

But Qualcomm has a giant wall of patents on display at their headquarters in San Diego and that doesn't inspire much confidence.

I should be clear too, I don't actually use Arduino hardware, only Raspberry Pis and ESP32 based boards. However, I've done a couple HackerBoxes which use the Arduino IDE a lot. I wonder if HackerBox will still base their tutorials around that going forwards. Either way, this is a sad turn of events and I am happy to be moving further away from the ecosystem with the change over to Rust.

Anyways, back to talking about learning a new programming language.

Why did I fail at learning Rust in the past?

I liked the idea of Rust since the project was first announced and I followed it closely all these years. Even waaay back when rust had different pointer types with weird symbols. Yet time and time again I bounced off it an never really learned enough to be productive. Sure I could do little toy programs, or finish Advent of Code problems, but that's not really knowing a language.

With other languages I can usually learn how to use it and hack away at a fun project at the same time. With Rust that didn't work for me and yet I kept approaching it that way. I should have known better, considering learning Haskell was the same. [4] Learn You A Haskell is what got me productive with the language back in college.

To be honest, I think it was a matter of hubris. The assumption I could just quickly pick up Rust since I knew other languages. Rust does a couple of things differently, and I love it for that, but it means I need to devote a little more time to really make sure I understand everything.

On mastery learning and stretching with deliberate practice

This is the section where I toss out the buzz words.

Despite enjoying math, I had a really hard time learning it growing up. In part this was because I moved up to honors math at one point. The paces between different course levels was different and so I missed a couple of sections. So I had to rush learning some pieces and they were a bit shaky. [5] Then I had to learn more on top of that shaky foundation so the new sections were also shaky. Rinse and repeat and somehow I finished differential equations in college, but left feeling like I was only going through the motions.

Then a couple years ago I heard Sal Khan talk about Mastery Learning and it all made sense:

Mastery learning simply means allowing a student to continue to work on a concept until they can master that concept or skill. You can tell a student has mastered a skill when they apply that skill to successfully complete a job, or task, that requires that skill.

Growing up I essentially did the exact opposite of that with Math.

Anyways, my previous attempts at learning Rust were scattered and I plan to be more thoughtful this time. Especially making sure I actually understand each piece before continuing.

I'm also going to take another term, this time from Cal Newport's book So Good They Can't Ignore You:

"In the early 1990s, Anders Ericsson... coined the term “deliberate practice” to describe this style of serious study, defining it formally as an “activity designed, typically by a teacher, for the sole purpose of effectively improving specific aspects of an individual’s performance.”

Additionally, when it comes to deliberate practice you need to find the right balance of how difficult it is:

"Doing things we know how to do well is enjoyable, and that’s exactly the opposite of what deliberate practice demands…. Deliberate practice is above all an effort of focus and concentration. That is what makes it “deliberate,” as distinct from the mindless playing of scales or hitting of tennis balls that most people engage in."

"I like the term “stretch” for describing what deliberate practice feels like, as it matches my own experience with the activity. When I’m learning a new mathematical technique—a classic case of deliberate practice—the uncomfortable sensation in my head is best approximated as a physical strain..."

"Pushing past what’s comfortable, however, is only one part of the deliberate-practice story; the other part is embracing honest feedback—even if it destroys what you thought was good."

and from his book Deep Work:

...what deliberate practice actually requires. Its core components are usually identified as follows: (1) your attention is focused tightly on a specific skill you’re trying to improve or an idea you’re trying to master; (2) you receive feedback so you can correct your approach to keep your attention exactly where it’s most productive.

Smooshing together ideas from those books and Slow Productivity, a rough sketch for my personal plan looks like:

- Regularly block off time when I can sit down to learn Rust. Don't just assume I can magically find time in the week. I know I won't.

- Understand that I can't focus indefinitely and only block off a reasonable amount of time followed by breaks.

- Regularly practice over time rather than trying to cram. [6]

- Structure the practice so that I can quickly get feedback as I go. Problem based exercises are a great way to do this for programming languages.

- Progress through problems so they stay just hard enough, "comfortably uncomfortable":

- Not so easy its rote and I can't stretch.

- Not so tough I spin my wheels and give up.

- Work up through more complexity as I master concepts.

Easy right? The great news is there are some wonderful resources from the Rust community for learning.

The road map is:

- The Rust Programming Language book and Rustlings, which are both completely free online, to learn the basics.

- Command-Line Rust, which is DRM free on Bookshop.org, to make small single process programs.

- Rust in Action, to practice systems programming.

- Asynchronous Programming in Rust, which is available on packtpub DRM free, and the Async Section of 100 Lessons to Learn Rust

- Zero To Production In Rust, which involves writing an email newsletter service from scratch and teaches the pieces like CI.

- The Embedded Rust Book, which is completely free online, to get the embedded pieces.

I want to be clear I'm not trying to be prescriptive to others. Rather, I want to describe what I plan to do, and how that goes. Hopefully that can act as inspiration for others to design their own road map for their own needs.

Finally, I should note I am making sure all AI suggestions and auto completion turned off. Practicing recall is important for concretizing memory.

The Rust Book and Rustlings

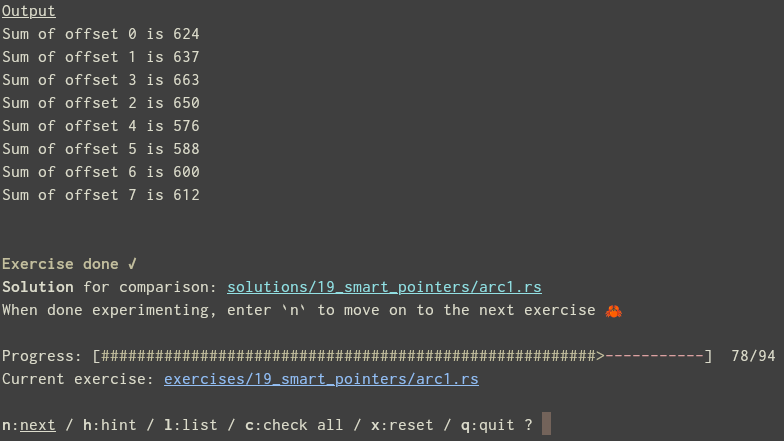

Rustlings is a very cool project. There's a tool you use to generate the project directory and interact with as you go:

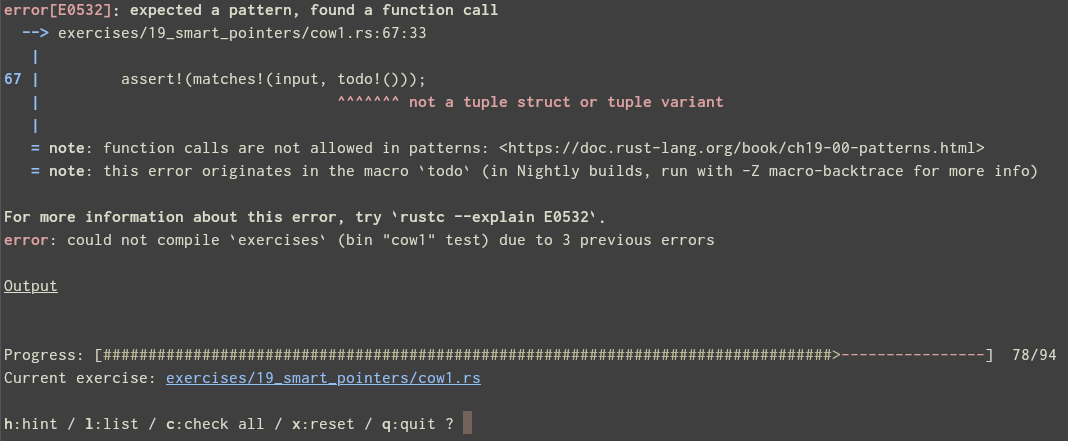

Each exercise is written with Rust tests to check if you have solved the problem. The interactive tool will compile and run the test automatically as you update the exercise, and show you the error messages:

You can also get problem hints and when you finish the problem you can see the example solution.

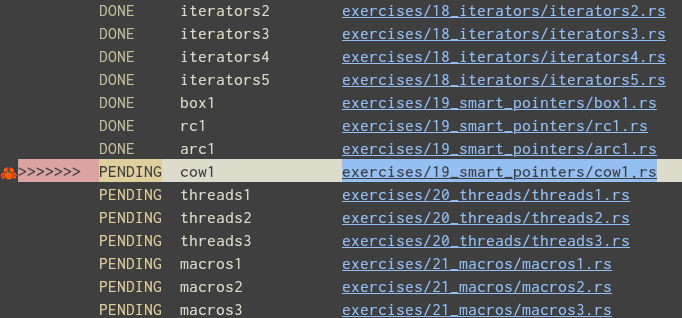

The exercises are organized by topic and each section is pretty small. This makes it very manageable to block off small periods of time to work through the book. Also, each topic includes a readme with links to important sections in The Rust Book. This is great because in the past I had tried reading The Rust Book front to back and failed at that. A more exercise driven tour through, combined with looking up sections when needed served me better.

I'm almost finished with all the exercises, just leaving the last couple around threading and macros until I've done a bit of Command-Line Rust. I have a repo with my solutions for the problems.

Command-Line Rust

I've only just started working through the book. [7] I skimmed the preface and chapter 1 since there is a lot of overlap with the Rust Book.

Each chapter covers a different Unix coreutils program and starts with an explanation of how the command works. So a nice side effect is getting to learn the internals of common unix programs like echo and cat. Also basic Unix concepts like exit values.

Then you are walked through recreating a subset of the command's behavior with Rust. The book introduces writing tests basically from the start, which is a nice way to build on top of what I learned from Rustlings. The author has scripts you run on your machine to save the output of the command you are duplicating. Then the tests will compare those outputs to your implementation which is pretty slick.

The author's solutions are on GitHub for reference and I'll push my own after I get further into the book.

Closing thoughts

I've enjoyed the resources I've gone through so far and I'm excited to get to the rest. As expected, the only difficulty has been blocking off the time to work through everything. I'm hesitant to post this and never follow up, but in a way this post should act as a form of accountability.

🦀

Since its very easy to make claims about what you are going to do and never follow up on them. ↩︎

In general, I'm a fan of how the whole MetaLanguage family feels. ↩︎

Trig still really gets me because of this. ↩︎

Related, I once did this Coursera Learning How to Learn, which touched on this point. I feel like its the kind of topic we should probably all be taught at a young age to prepare us for school. ↩︎

The book was originally released in 2022, but I used the updated version from 2024. That version provides an opportunity to learn the clap crate. ↩︎

Member discussion